By Captain John W Papciak

Another season is upon us and many would argue it's a bit ahead of schedule, It's all the more impressive how most experienced anglers talk of a clear plan for what they will be doing over the next 4-6 weeks and the 4-6 weeks after that. In fact, many have a playbook dialed in for a combination of lunar phase, tide, wind, and so forth. We do accept that each day will be different, and that each spring and fall run will be different. But there is a clear expectation that fish will show along given parts of the coast, on or about specific dates.

It is not a stretch to believe that a migratory gamefish is genetically programmed to pass through at a certain time on the calendar, and along a certain route, where it is most advantageous to encounter food along the way. The best fishermen I’ve ever known spent much of their time asking “why are they here, and why now?”, instead of just accepting a good bite for what it is.

Plug bags and fly boxes are filled with specific shapes and colors, based on the most likely bait species to be encountered for the next couple of weeks. Size, profile and color need not be a perfect copy of a bait, but I’ve never met a successful fisherman who wasn’t super focused on matching the likely food source.

Creating Your Own Salt Hatch Chart

Most readers recognize the term ‘match the hatch,’ which describes the selection of lures or flies to imitate specific saltwater bait species. It’s actually a misnomer when it comes to the salt - nothing is ever ‘hatching’ - but everyone still gets it.

Our saltwater lure matching is not so different from what is done on a trout stream, though for freshwater it’s a much more refined process. As the bugs on the river develop wings and come to the surface, it’s impossible to miss. Floating dry flies are crafted to match every species in fine detail, though the debate rages on as to whether more general sizes and profiles might work just as well.

The bug nerds of generations ago noted how certain insect species preferred specific water and air temperature ranges. The end product was a schedule of hatches lined up on the calendar, and often tuned to very specific regions of the country. The best bug watchers have it dialed in for a specific river, though in every case there is a universal understanding that unusual weather (and water) can bump the schedule up or back.

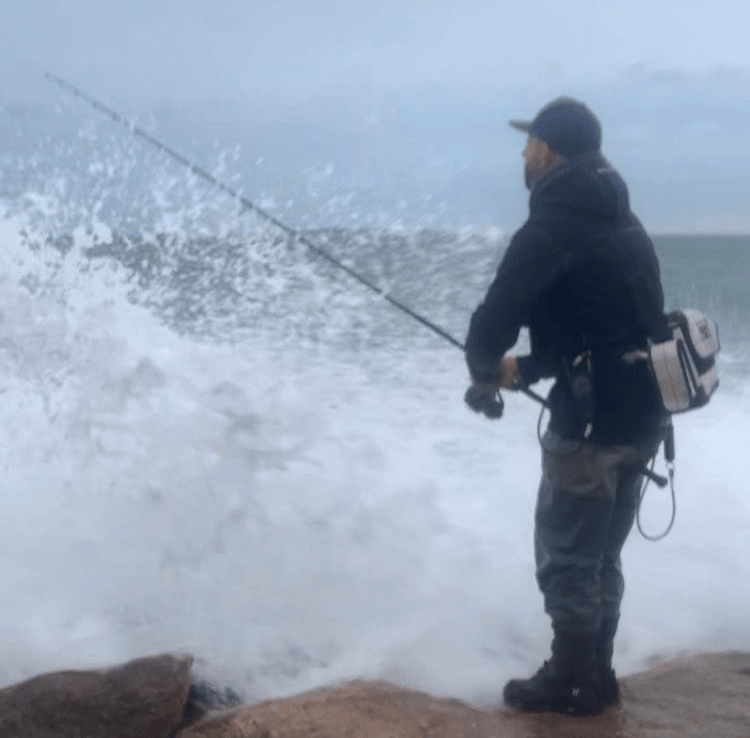

Image Courtesy of Northbar Media

Saltwater might never be so precise, but I am 100% confident than most or all bait species follow their own calendar. The ability to maintain a list of what bait species you might expect as the season progresses is probably just as important as learning to fish around tides and moon phases.

Deja Vu All Over Again

Perhaps it’s best to start with examples, based on some of the waters that I know best - the bays behind the Jones Beach Barrier Island.

I know I’m going to fishing with small spearing imitations by early April. Adult menhaden and squid tend to be found soon thereafter. I’ll be looking for small sand eels by early June, particularly closer to the inlets. Various young of year species - from fluke to baby bluefish - will grow over the course of the summer. Cinder worms can show, particularly around the high tides on the moons in June and July. Grass shrimp might be observed as well. Mullet will start to school by Labor Day. Snapper bluefish will be large enough to do much of the chasing come late August, though I’ll be on the lookout for evidence that the snappers themselves are being chased over the first days of September - as larger bluefish and bass tend to move up into the bay over this period for just this reason.

By contrast, what I’m expecting to see near Montauk Point over the course of the year is quite a bit different. Sand eels can be particularly important from Memorial Day through July. Bay Anchovy can feature from Labor Day to October, with juvenile peanut bunker often showing up later in the fall. The late season herring runs - from Thanksgiving to mid December - are not what they once were, though we still hold out hope of a return to the good old days of herring blitzes under the first snow squalls.

The main message here is that we can’t afford to generalize as much, likely due to the extreme variability of the waters and places we fish, whether it be the back bay or open ocean. Yet, in most cases, there is indeed a bait schedule, and it clearly explains why we do see so many of the same patterns year over year.

The “Big Three”: Sand Eels, Bay Anchovy and Peanut Bunker

Just like in freshwater, there is a very long list of possible bait species that can be encountered, but there are a number of dominant species that consistently drive the tempo of fall fishing at a place like Montauk.

If I had to name those baits that you *must* plan for while fishing the surf and inshore waters in the fall in Montauk, it would be Bay Anchovies, Sand Eels and Juvenile or ‘Peanut’ Bunker.

Image Courtesy of Northbar Media

Bay Anchovies tend to show up around Labor Day, and will congregate in significant numbers in the rips - and hopefully the surf - by mid September. False Albacore and Striped Bass tend to be highly selective in calm clear water, much less so in a chop. My logs show years where the “white bait” moved out by late October, after a storm, but we’ve observed anchovies holding small bass in the rips into November over the past couple of years.

Sand eels are one of those species that play an important role in spring *and* fall. The spring run of tiny (two to three inch) individuals can fuel excellent surf and inshore action the entire month of June, though I’ve followed them in the boat a few miles off through July. Sand eels often reappear in larger form by late October. Sand eels featured heavily in Montauk from late May to mid July in 2022, but only played a minor role in the mid to late October bite around the Point last fall. But there were a handful of days of fantastic fishing on the fall sand eel bite. By contrast, in 2018 we had a steady sand eel bite tight to the beaches on the East End until mid November. As many others have written, sand eels often remain stationary for days at a time, making this bait one of the best species for predictable day to day in-shore and surf action.

Peanut bunker are usually observed in the salt creeks and back bays by August. They can begin migrating out into open water at various times, though mid October is a good time to keep an eye out for them. With any luck some of these schools remain close enough to shore by late October and early November, as was the case in 2019. In fact, that year there were a number of days where both bay anchovies and peanut bunker were simultaneously fueling blitzes within sight of the Montauk Lighthouse. Year to year variability can be significant, even for the most dominant bait species. My logs mention excellent peanut induced surf action around 2004-2006 in places like Napeague and Georgica Beach right up to the week before Thanksgiving.

The Other Important Baits: Mullet, Bunker (Adult) and Herring

The most obvious baits that fall into this category are adult menhaden, adult herring, and mullet. Of course, these bigger baits have triggered legendary blitzes in the Montauk area - and will continue to do so - but as of late most anyone on the water will report just as many days of these bait fish moving by unmolested.

Mullet tend to be tied the most to the calendar, usually moving between the third week of September and early October as the first cold fronts of the season pass through. Herring were traditional arrivals the week before Thanksgiving, bringing the last push of large bass of the fall run. Adult menhaden, on the other hand seem to move on their own schedule, though the timeline provided here is a general guide. In any case, it’s still important to have larger, wide profile patterns close at hand on every trip.

The Best of the Rest: Cinder Worms, Hickory Shad, Squid, Baby Bluefish, Baby Weakfish

The next-in-line important bait species to be aware of can go on for pages. I include certain species in this essay because of the epic fishing that they’ve provided at various points over the years.

There can be a short but very exciting run of juvenile weakfish around the point that often coincides with the full moon of late September or early October. The aforementioned cinder worm hatch is generally confined to the back bays around the new or full moon high water change in June or July. Incidentally I did have an epic night on a worm hatch one year in July in a salt pond on Nantucket. Hickory Shad can move through in early May, and then again in November, along the open beaches. This bait was responsible for that one night in May some years ago in Montauk where I only caught three fish in the surf, but each was in the 40 pound class. Squid are an important species in New England, and I seem to find them more often being chased by striped bass in May and early June, and then again in October. Chub Mackerel deserve a special mention here as they have been seen more frequently over the last couple of seasons, and they do have a tendency of attracting the largest bluefish and striped bass (as well as sharks). Last but not least we have snapper blues, which are usually funneling out of the bays on almost the same schedule as mullet.

Getting Dialed In to Your Own Waters

Image Courtesy of Northbar Media

There are additional resources to get you started on your own chart. The most common way to confirm bait is to have a fish spit up its most recent meal. It might be taboo to ask a fisherman if he caught any fish, certainly not where, but I usually get candid and detailed responses if I just ask if he saw any bait. If you can’t see the bait in the water, the presence of cormorants or gulls is usually a good sign that there must be something around. If you take the time to watch birds working, you’ll almost always see what’s got their interest. Some bird migrations are driven by seasonal bait migrations. In most cases the bird species and the pattern of flying and diving will reveal the type of bait below the surface. The sight of terns working over small sandeels in June is something that every inshore fisherman should commit to memory.

We’ve only scratched the surface here, plenty more to say in a future update.

Leave a comment (all fields required)