Photo and article by Ed Mitchell

Photo and article by Ed Mitchell

Have you ever hooked a big bass from the beach—one of 20 pounds or more? If the answer is yes, you already know it’s quite a rush. The power, the sheer weight, the sight of that shovel-shaped tail slapping the surf—it's unforgettable. If the answer is no, well, sit back and read on; I'll help you change that.

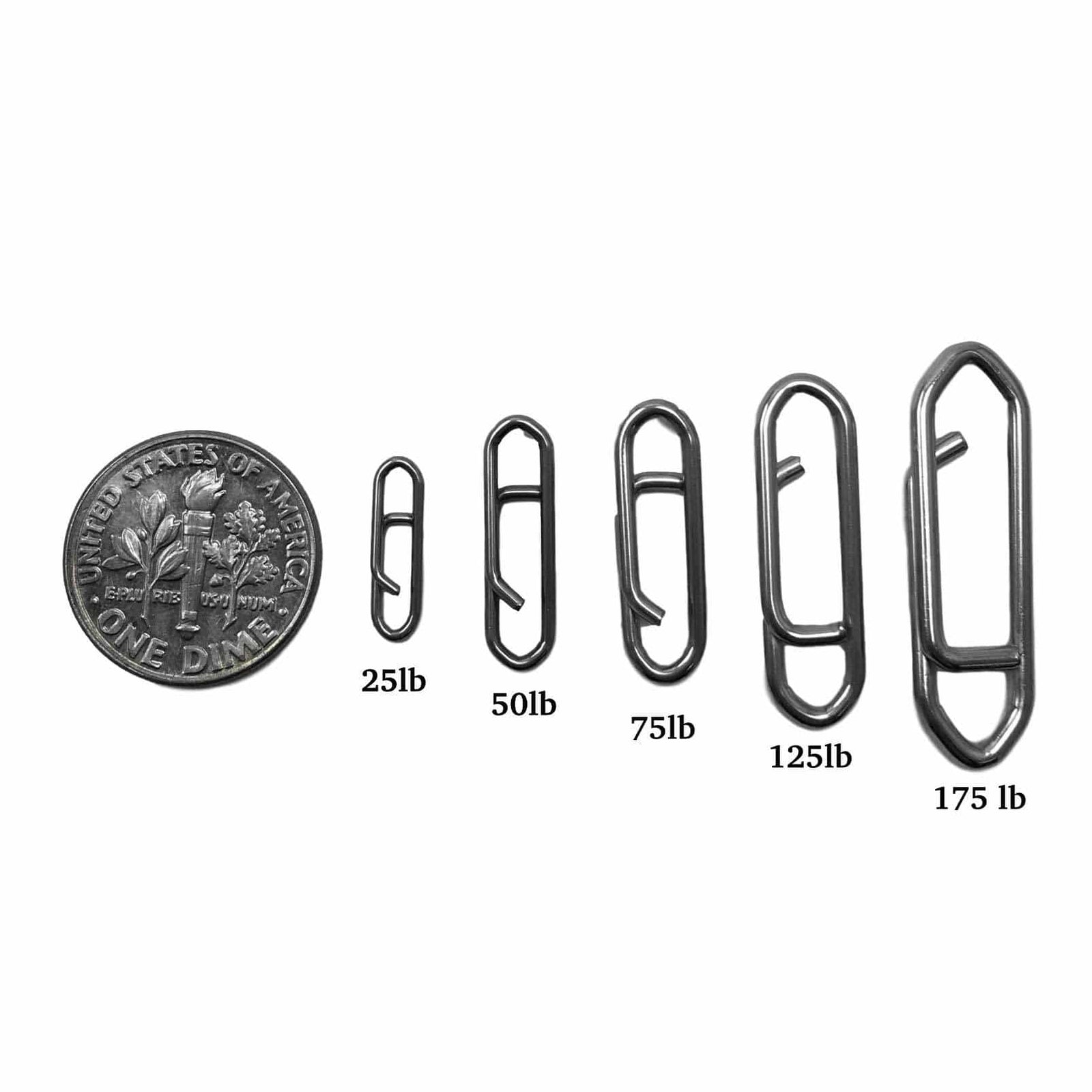

Plenty has already been written about the fundamentals of "how to" catch a big bass on a fly rod. So, you have already heard about the benefits of larger flies, the need for sharp hooks and strong knots, and so on. Consequently, I assume you either know those things or can find that information elsewhere. That will free us up to focus entirely on one critical aspect of the hunt for big bass: where and when to find them. But before we tackle that, let's get one thing straight. No theory will ever pinpoint exactly where and when big bass show up. Still, what I am about to tell you can go a long way to swinging the odds in your favor.

Good Scouting Tides - How has your beach changed this winter?

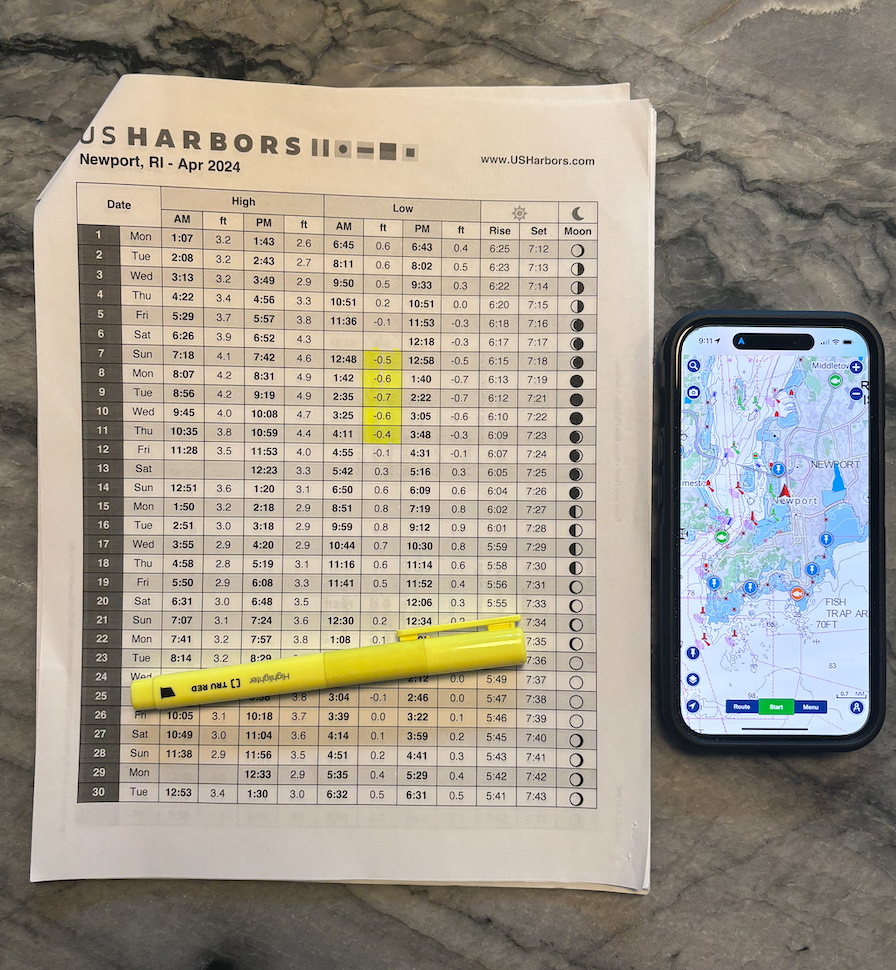

You will need two things to follow along in this discussion. First, get a comprehensive tide book (or software), one that has not only the time of high and low, but the various moons, and the height of the tide as well. I recommend the Eldridge Tide Book if you're looking for a suggestion. Second, you should have detailed charts of your favorite coastline. Got them? Then let's go.

When to Hunt for Big Bass

Given the pressures of the workaday world, most anglers fish a limited number of times per year. As a result, the single biggest obstacle they face is deciding how to plan their time on the water wisely. Now, if you're satisfied with schoolie bass, that is not very hard to do. But when yearning for a bass longer than a yardstick, you best put your thinking cap on. And the place to begin is by identifying which months hold the best fishing for big bass in your part of the coast.

Season

A big bass could latch onto your fly at just about any time of year, but far and way, the most productive moments for a jumbo striper from shore occur during the annual spring and fall migration. Each of these periods is roughly six weeks long, yet in both cases, it is toward the end of that migratory surge that your big bass chances are best of all. Why? Big bass are the last to leave the spawning grounds and, therefore, the last members of their tribe to hit the coastal highway. As a result, these fish are not mixed in with the first surge of stripers that shoots up the coast in the spring. And because of their cold water tolerance, they are also the last ones to head home in the fall.

So, we have roughly a month-long window of opportunity in the spring and another month-long window in the fall. In southern New England, that translates from late May to late June and again from late October to late November. If you fish further north or south, obviously, you have to adjust. For example, on the fall end of things, in New Jersey, it is early November into early December. While up in Maine, it would be early September into early October.

The Moons of Migration

At this point, we have our hunt for big bass narrowed down to a 60-day season—manageable. Now, let's try to take it a step further. Inside those two month-long windows, there are peak periods, times when the odds tip further in your favor. When are they? Striped bass seem most active around the stronger tides of the new and full moons. Therefore, fishing during these moon tides increases your odds of meeting up with a big, hungry bass.

Open your tide book to the months in question and mark the day of each of these migration moons. (In the Eldridge, you'll find the days of the moon listed in the back often on page 233) For example, in Southern New England you would check off the last moon of May and the two moons of June, followed by the last moon of October and the two moons of November. Remember, as mentioned before, you must adjust this region by region. For instance, if you are fishing in Maine, I suggest the two moons of September and the first moon of October. On the outer beaches of Cape Cod during the fall, I would pick the last moon of September and both moons of October. While on the south shore of Long Island, I would opt for the moons of November. Further south at Sandy Hook, New Jersey, the migration is later; hence, it would be the moons of November and the first moon of December.

The next step is to note that each moon hosts upwards of six days during which the tides are above average in height. Circle these days in your tide book. You now have defined approximately 36 prime days to meet up with a trophy bass. By the way, if any moon does not host above normal tides, that moon is in apogee. Apogee moons are those that occur when the moon is at its maximum distance from the earth. Unfortunately, an apogee moon tide is really no stronger than a quarter moon tide. Therefore, I suggest you cross that moon off the list. My guess is that you will lose at least one of the six moons you checked off, thereby reducing your prime day total to 30.

Weather

Besides adjusting by region, you need to adjust your fishing around the weather. As a rule, warmer weather makes for a longer season by kick-starting fishing earlier in the year and delaying the return to the south—a slightly cooler spring delays good beach fishing by a week. An even colder spring, however, may set beach action back two weeks or more -- as many anglers discovered this year. Conversely, a chilly fall means the fishing starts and ends earlier than usual. A warm fall is the reverse.

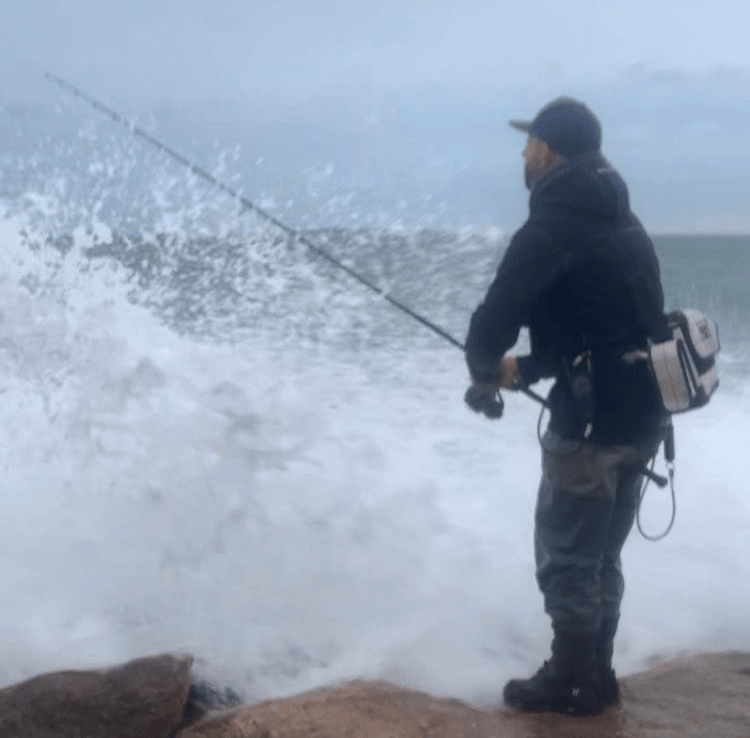

Furthermore, in either spring or fall, the approach of a strong storm can trigger a brief but memorable blitz. In the spring, these are likely thunderstorms, and in the fall, they're apt to be Nor'easters. Naturally, in both cases, your personal safety is item one, so use common sense.

Time of Day

It is common knowledge that beach-bound anglers do better on big bass during low-light conditions. Therefore, any outing you attempt during those 30 prime days should concentrate on dusk, dawn, or night fishing. Naturally, you'll base your decision on the tide of the tide. Nevertheless, when all things are equal, in my experience, dusk is a bit better than dawn in the spring. Yet, in the fall, dawn is undoubtedly the better of the two. On the night fishing end, during the spring migration, late-night tides -- those that occur between 11 PM and 1 AM -- are superior. In the late fall, that has never seemed to be the case. At that time of year, early evening tides or just before first light seem to have the edge.

Which is more productive at night, a new or the full moon? I have expressed my opinion many times on this question, but it bears repeating here. I think the answer depends on the depth of the water you intend to fish. Shore-based anglers typically work in relatively shallow locations. Here, a new moon is best. Why? In these locations, the light from a full moon penetrates a fair percentage of the water column, discouraging big bass from aggressively feeding. Over deeper water, however, the light from the moon does not reach the fish and hence is not a problem.

Where to Look

How do you have a good idea of when to fish? All that remains is to decide where. So, break out the charts. It is a cruel fact of life that quality and quantity rarely go hand in hand. And striper fishing is no exception—a place where you regularly bail schoolies is usually not a place to catch bruiser bass. So, focusing on the big bass usually means forgoing the steady action supply of the smaller bass. This is a bitter pill to swallow; in fact, many anglers can't bring themselves to do it. Understandable. But if big bass are your game, you must take the medicine.

The Hunting Grounds

Overall, this means avoiding extremely shallow shorelines or very warm water. Instead, lean toward windy, exposed locations with some depth or at least deep water nearby. These are more likely locations. Moreover, the migration of big striped bass is often closely coordinated with the migration of key forage fish. Therefore, large bass are frequently found where schools of migratory forage fish tend to congregate. Two types of shoreline areas fit this to a "T." Inlets and river mouths, along with their adjoining beaches, are one of them. The other one is points of land.

With your charts open, circle the various inlets and points within driving range. Now look back to your tide book and look up the time of tide for these spots during the prime days we discussed, and particularly how these tides relate to dusk, dawn or night. With the inlets and river mouths, you probably want an ebbing flow, but remember that the current may start one, two, or even three hours after the time of high tide. The right tide for a point of land is hard to generalize. Some fish better on the flood, some of the ebb. But whatever you pick, once again, note how the time of tide compares to the light level.

In the spring, inlets and river mouths usually out-produce the points, so focus your energies there. In the fall, however, things are different. Typically, these forage schools first show up in the inlets and river mouths. After a time, they move to the adjacent beaches and stage off the points before finally migrating away from shore. Try to follow along.

The Elephant In The Room

Striped bass have adapted themselves over thousands of years to the Atlantic seaboard's prevailing water temperatures, tides, and weather. As a result, their migration patterns are reasonably predictable. Granted, minor changes occur now and then, but still, there is a clear pattern to follow. Unfortunately, climate change is on our doorstep and has the ugly potential to alter how and when striped bass migrate. It’s a fact we must face.

The truth is that migratory wildlife are the most vulnerable animals to climate change. Because of this, wise anglers need to remain observant and willing to adjust in the years ahead. This impacts not only striped bass but all migratory fish along our coast. They may come north sooner, leave later, pick new spawning grounds, and pick new preferred places to hang out. We are very likely to see new species competing for the same habitat and forage.

About The Author

Around the age of fifteen Ed Mitchell picked up his first fly rod. And it’s been a love affair ever since.

Ed is the author of four books – Fly Rodding the Coast, Fly Fishing the Saltwater Shoreline, Fly Rodding Estuaries and Along the Water’s Edge.

Ed's Tide Log

He's also been a contributing editor to Fly Fishing In Salt Waters magazine and over the years, penned articles for every major fly fishing periodical including –American Angler, Fly Fisherman, Fly Tyer, Fly Rod & Reel, Fly Fishing in Salt Waters, Saltwater Fly Fishing, Saltwater Sportsman, and Tail Fly Fishing. And more recently Martha’s Vineyard Magazine. Find examples here

Ed maintains a very informative blog edmitchelloutdoors.com Check it out!

Dejar un comentario